Related coverage

- Henderson settles lawsuit against would-be sports arena developer (3-14-2013)

- Developer denies ‘deal’ was reached with stadium promoter Milam (3-01-2013)

- Henderson alleges Milam had struck secret deal to develop homes on stadium site (2-28-2013)

- Brochure advertising proposed stadium land for sale leaves officials scratching their heads (2-25-2013)

- Closing date delayed for land sought in Henderson arena deal (2-05-2013)

- City alleges developer with arena plan only wanted cheap land (1-29-2013)

- Henderson City Council lets stadium feasibility study move forward (9-06-2011)

- More business news

Building a professional sports arena or stadium without a team committed to play there is practically unheard of.

Developer Chris Milam wanted to build four of them — and got the Henderson City Council’s full support.

There were plenty of red flags when Milam pitched his proposed Las Vegas National Sports Complex, but city officials either failed to recognize them or ignored them.

The city eventually sued Milam on fraud charges. As part of a settlement reached Tuesday and finalized Thursday, he is barred from working on future developments in Henderson.

It’s nearly impossible to finance a speculative arena or stadium, let alone a cluster of them as Milam envisioned. Also, the project's main financier reportedly was a Chinese surveillance-equipment maker, not a well-known stadium construction lender, such as Goldman Sachs or Bank of America.

In the end, no teams committed to the facility, and Milam’s group was sued in late January for allegedly trying to flip the government-owned project site to other developers.

Sports industry executives outside of Nevada laughed at Milam’s stadium plans when contacted by VEGAS INC this week.

“If these are truly major league sports facilities, doing one of them by itself would be an unbelievably difficult task, much less four,” said Jack Hill, project executive for the new San Francisco 49ers’ stadium being built in Santa Clara, Calif.

Milam’s project would have cost at least $2 billion, industry consultant Michael Rapkoch estimated. Rapkoch said he’s “perplexed” the project progressed as far as it did and did not receive closer scrutiny.

“I’m baffled by your city government,” he said.

Milam claimed he negotiated with team owners and league commissioners to lure franchises to his venues.

But pro clubs typically have long-term leases that are expensive to break, making it difficult for teams to move. League officials also are wary of letting teams play year-round in America’s gambling mecca, which is part of the reason Las Vegas currently has no major league teams.

As Rapkoch sees it, Henderson officials failed to thoroughly vet Milam’s plans.

Rapkoch's Texas-based company, Sports Value Consulting, assesses team values for prospective buyers, some of whom claim to have financing sources in China. When he asks to speak with those bankers, he never gets a call back, he said.

“There’s a lot of that going around,” Rapkoch said of the China claims.

Around the country, speculative facilities occasionally are proposed but rarely are built. John Loyd, an Alabama consultant who helps build and renovate pro stadiums and arenas, could name only one purely speculative facility built in the United States: the Alamodome in San Antonio.

That arena, owned by the city of San Antonio, opened in 1993 to lure a National Football League team. It never got one.

Today, the $186 million facility is used for trade shows, conventions and performances.

Almost no one would lend hundreds of millions of dollars for a speculative facility “and not have some expectation of how they’re going to get their money back,” Loyd said.

When told that Milam planned to build four speculative venues, Loyd chuckled, saying he’s never heard of that kind of project.

“That would be most unusual,” he said.

•••

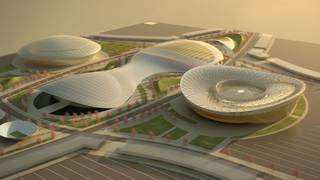

Milam laid out plans to build an arena and three stadiums on 485 acres of desert owned by the U.S. Bureau of Land Management. He sought to buy the site near the M Resort through the agency’s auction process.

Initially, he received little skepticism from City Hall.

The Henderson City Council in September 2011 unanimously approved a preliminary project agreement with Milam’s group and gave their full support to the BLM land sale.

Councilman Sam Bateman commended Milam and city staff for drafting the project agreement and said the complex is critical for the region.

Councilwoman Kathleen Vermillion lauded Henderson for having a “we can” mentality. She thanked Milam and city staff for pursuing the project.

A few council members had questions about the project’s financing, but no one voiced skepticism about the likelihood that Milam could build such a massive, speculative development.

“I’ve said it all along: What community, what mayor wouldn’t want a project like this in their city?” Henderson Mayor Andy Hafen said last April, after a council meeting in which Milam declared project financing was fully approved. “We’ve done our due diligence, and we’ll continue to do our due diligence. I think that if things fall into place and we get this thing going, it will be a boon for Henderson for years and years to come.”

Milam proposed his project during the recession when there was little other activity in Henderson.

“I think it's something the city (had) to listen to,” City Attorney Josh Reid said this month.

Reid, who became Henderson’s top lawyer four months after the council approved Milam’s plans, said city officials tried to vet Milam’s claims. But “most of the information was held by him and his investors,” Reid said.

For instance, Milam claimed he worked with investment firms Morgan Stanley, Goldman Sachs and Piper Jaffray to arrange financing. The firms, however, never committed to the project.

“We know that now,” Reid said.

Hafen and council members Bateman, Debra March and Gerri Schroder, who all approved Milam's plans and remain in office today, did not respond to requests for comment. Vermillion, who resigned from her seat in December 2011 and later was investigated by the FBI for allegedly misusing money from her charity, could not be located.

Milam attorney Terry Coffing said his client would be the first to acknowledge that the project was risky, but Milam felt that if he made enough progress on construction, he could have landed a team.

Coffing said Milam spoke many times with National Hockey League officials about getting the league-owned Phoenix Coyotes to move to Henderson. If that worked out, Coffing said, Milam also could have landed a National Basketball Association team, as the two clubs could have shared an arena.

“It’s kind of a chicken and egg philosophy: If you build a stadium, they’ll come,” Coffing said.

NHL spokesman Frank Brown declined to comment, saying the league doesn't disclose with whom it does or doesn't speak.

•••

Milam started planning the stadium project in 2009. He felt his arenas could replace the region's aging venues, including Sam Boyd Stadium, the Thomas & Mack Center and Cashman Field, all of which are at least 30 years old.

NBA, NHL and Major League Soccer commissioners also “appeared to be warming” to the idea of having teams in Nevada, despite the state’s legalized gambling, according to court papers filed by Milam's legal team.

Milam initially tried to build an arena or ballpark in several other parts of the valley, including near the Strip, but his plans fell through. He launched discussions with Henderson city officials in summer 2011.

With the region decimated by the recession, the project’s estimated financial impact was likely alluring. Construction alone was forecasted to bring almost $1.5 billion of activity to the city, and the complex’s annual operation would have produced another $515 million a year.

Milam also pushed a fast timeline. He initially sought to break ground in summer 2012, finish the arena in summer 2014 and hold the first NBA game a few months later.

By comparison, the 49ers’ new $1.2 billion, 68,500-seat stadium has been under construction for almost a year. It is expected to open in 2014 — after a decade or so of planning.

Despite claiming to work with powerhouse investment firms to arrange financing, Milam’s main source of funding ultimately was slated to come from China Security and Surveillance Technology. The company, based in Shenzhen, China, manufactures and installs security and surveillance gear.

According to Milam, the company agreed in spring 2012 to finance a $650 million, 17,500-seat indoor arena. It did not require an anchor tenant as a condition for financing. The company planned instead to charge a high interest rate of 20 percent.

A few months later, its board allegedly reversed course and decided they would finance the deal only if Milam lined up a team.

Milam’s group got furthest with a plan to bring the Sacramento Kings to Henderson, according to court documents. But that deal fell apart last year after the construction-financing terms were changed, the filing said. It also cited a “slow pace of discussions.”

Chris Clark, spokesman for the NBA team, would not confirm if talks were held. Representatives for China Security, Morgan Stanley and Piper Jaffray did not respond to requests for comment. Goldman Sachs spokesman Michael DuVally declined comment.

All told, Milam’s potential success with the project depended largely on whether he could get professional teams to move to Henderson — an unlikely prospect.

Only a few teams are candidates for relocation, and league commissioners are wary to allow expansion teams to pop up, said Dan Grigsby, chairman of the national sports law group at the Jeffer Mangels Butler and Mitchell law firm in Los Angeles.

“I don’t know where the teams would come from,” Grigsby said.